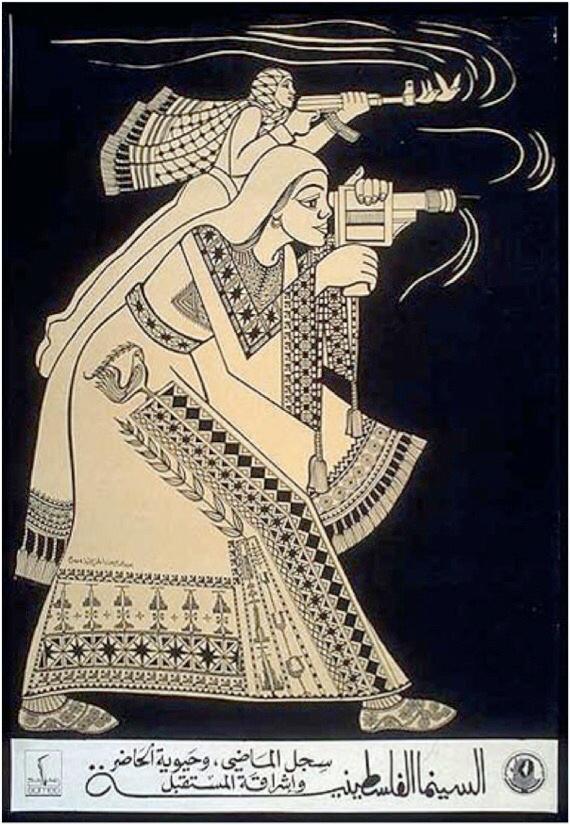

Palestinian filmmakers presented to the people of the world a combat cinema: facing the most complex adversities emerged a dynamic, immediate and authentic production, aware of their role, integrated with Palestinian resistance and national spirit in conformation - that Cuban filmmaker Santiago Alvarez characterized as “the first of all the revolutions that had cinema during the fight” 1 .

What is generally considered to be the origin of Palestinian militant cinema is the movement of independent filmmakers, mostly refugees, who have begun their aesthetic and filmic research with other Arab and foreign filmmakers. The movement began to crawl in Lebanon, in the cities of Amman and Beirut in the mid -1960s and unleashed in the 1970s until the mid -1980s - a chronology that corresponds exactly to one of the waves of the Palestinian revolution, which begins after the defeat Arabic in the six -day war in 1967 and ends with the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

However, even circulating in the Middle East and internationally, many of the films of this production have never passed in Palestine itself, due to the fierce censorship of the occupation. With regard to preservation, most of the originals are in poor condition, or were destroyed during the military forays of Israel.

Opening the Way: The Palestinian Film Unit

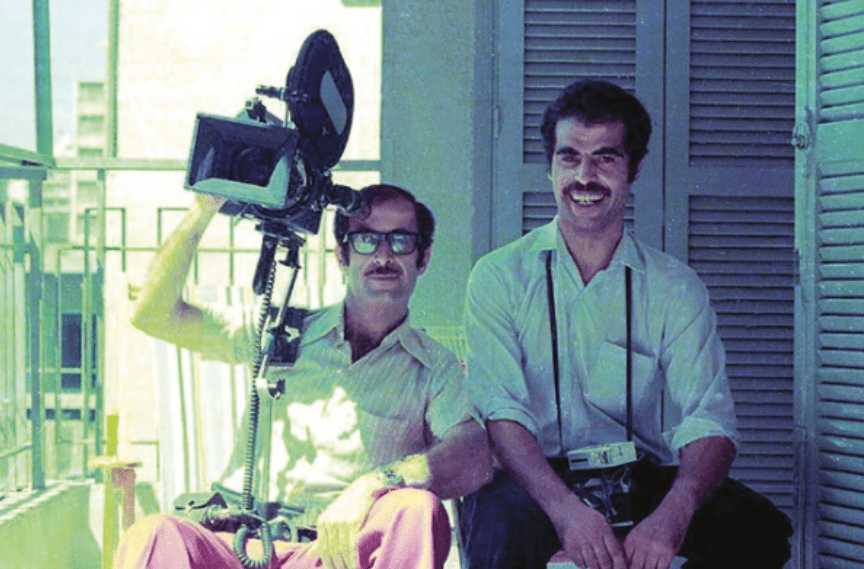

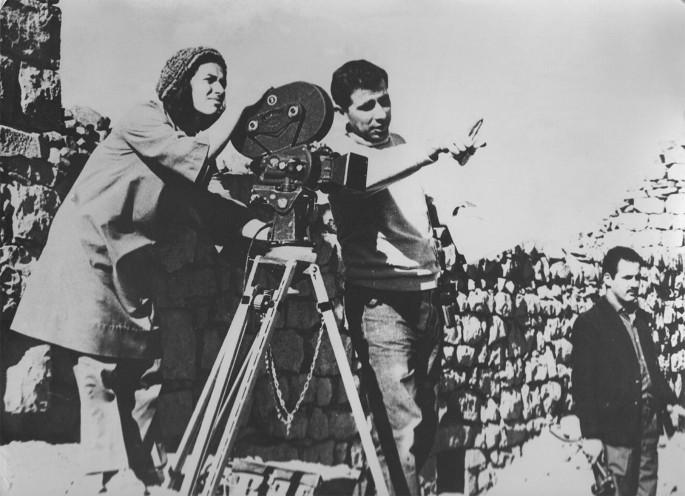

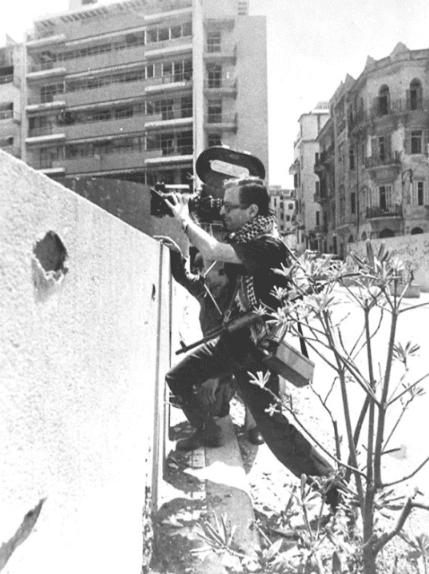

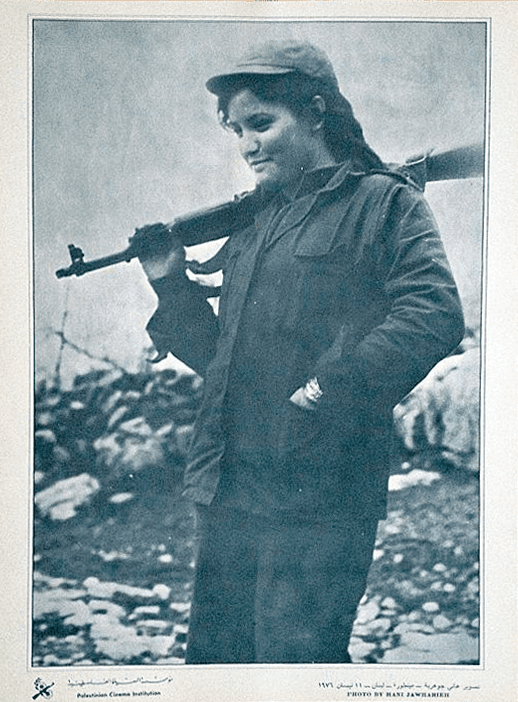

Among these pioneers, filmmaker Mustafa Abu Ali, photographer Hani Jawharieh, photographer Sulafa Jadallah (considered the first Arab cameraman), and later critic Hassan Abu Ghanima, are the most outstanding figures in the process of articulation of the first militant cinema Palestinian. The three worked together at the registration of the Military Operation of Palestinian Resistance in Al Karameh (1968), and Mustafa already had experience with cinema, having accompanied the French director Jean-Luc Godard during the recording of the movie "Until Victory".

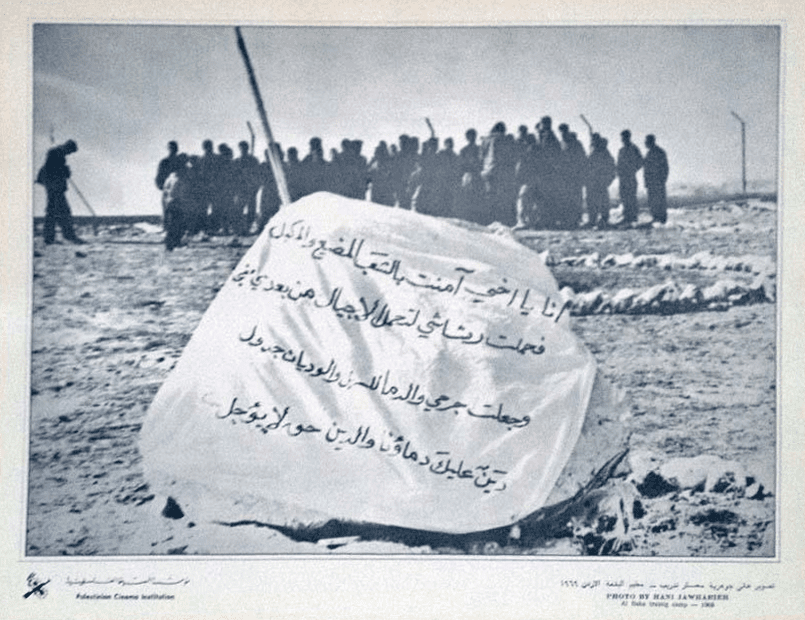

Working from within the Fatah Information Office Department, the three began to organize themselves as a Palestinian Film Unit (UCP), with the express objective of starting the construction of a large image file of the revolution. In the manifesto published on the occasion of the first Youth Film Festival in Damascus in 1972, affiliation was already clear: "Popular cinema must express the popular war."

UCP's first collaboration was the work: “Say not to the capitulatory solution!” (Mustafa Abu Ali, 1968), addressing Arab protests against the Rogers plan; And then, “with soul, with blood” (Mustafa Abu Ali, 1971). This joint effort to build a Archive of the Palestinian Revolution would lead to the Palestinian Film Group (GCP). GCP, despite its brief life, signing only one documentary, “ Occupation scenes in Gaza ”(Mustafa Abu Ali, 1973), produced a manifesto that demarcated the clearer position for the association and ideological solidity of the Palestinian filmmakers, as well as the direct incorporation into combat. The GCP established its headquarters at the Research Center for the Organization for the Liberation of Palestine (PLO); and later rearticulated as a Palestinian Film Institute (ICP).

“It is important, in fact, to develop a Palestinian cinema capable of supporting with dignity the struggle of our people, revealing the facts of our situation and describing the stages of the Arab and Palestine struggle for the liberation of our land. The cinema we aspire will have to devote to expressing the present, as well as the past and the future. Their unified vigor will imply the regrouping of individual efforts: in fact, personal initiatives - whatever their value - are condemned to remain inappropriate and ineffective. ”

GCP Manifesto, 1973.

In 1974, a year after the release of the Manifesto, Mustafa directed the documentary “ They do not exist “, Signed on behalf of ICP. The title of the film references a speech by Prime Minister Zionist Golda Meir (“Who are the Palestinians? I don't know any people with that name… they don't exist”) and Israel's Minister Moshe Dayan (“No more Palestine … She does not exist"). “They do not exist,” along with so many other films of the period, were considered destroyed after the Zionist attack on Beirut in 1982, and only passed for the first time in Palestine in 2003, when he was smuggled (along with the director) to the Film Festival) clandestine “dreams of a nation”, organized by director Annemarie Jacir 2 .

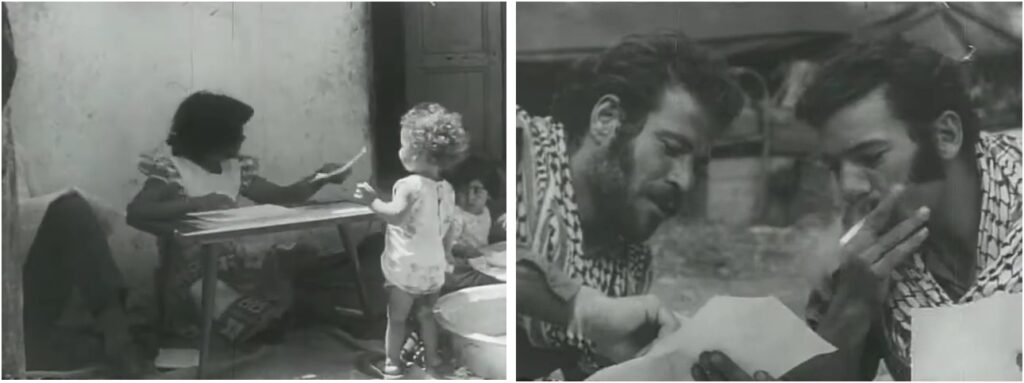

“They do not exist” pioneering the lives of Palestinian refugees in the Nabatiah Campo in southern Lebanon and his bombing in 1974; In addition to the daily life of guerrillas, locating them as part of the national liberation struggles from around the world. In a moment of tenderness that integrates these two elements, refugees prepare a gift bag to send to the combatants, and among them, a letter written by a 10 -year -old Palestinian girl who says “I'm sending a simple gift, a towel. Hope you like. I wish I could send something better, because you deserve the best, you sacrifice yourself for Palestine. ”

The "detachments" of filmmakers

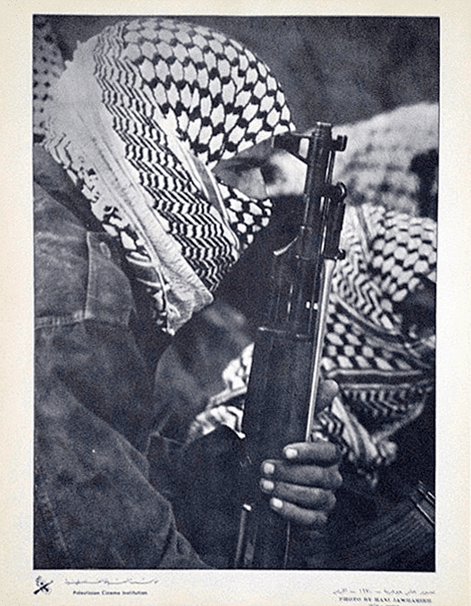

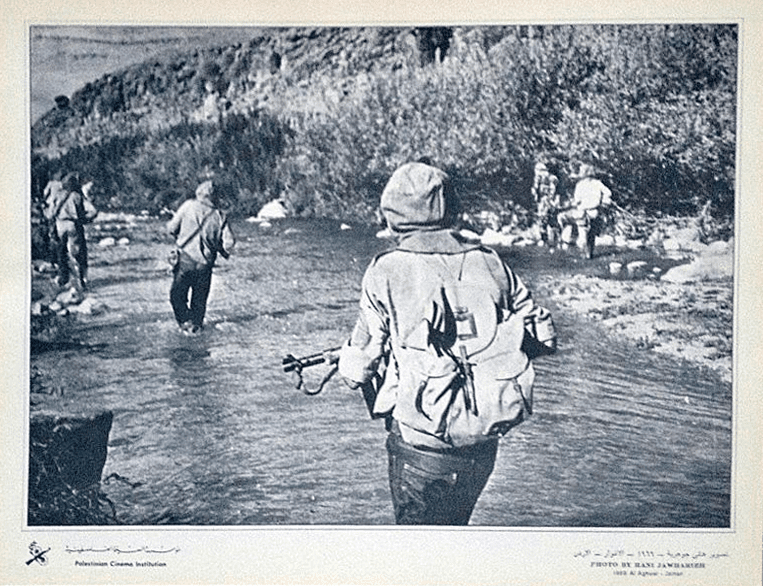

Organizing in small groups, carrying their light cameras like a “gun that fires 24 frames per second” 3 , the filmmakers operated as guerrilla units, claiming to be "from the popular war that our militant cinema takes the patterns of their work, as well as their inspiration" 4 .

That is: the movies were produced in the front combat, financed and distributed through the armed struggle support network and with the practice of circulating questionnaires by the hearing in the refugee camps after the films, to collect their impressions and better refine the work 5 , in a dynamic where “the relationships between the filmmaker and the masses must be continuous, pervading all the stages of the film's making” 6 , including the filmmaker's work to maintain the file, the distribution of films, the organization of festivals and screenings, the critical and theoretical intellectual work, etc.

As a consequence of the emphasis on the integration with the masses and the revolution, the effort would also generate a new film proposal, of “its own style, shape and its own, linked to the Arab inheritance and the specificities of the Palestinian Revolution and its particular circumstances”, with ““ methods adapted to the needs of the people in struggle to express their hopes and aspirations as accurately as possible ” 7 with a “clear aesthetic” aiming at a “popular cinema in which people are in the process of making the story” 8 . The dynamic character of the contract was thus stated: “We could not limit ourselves to a theory; It was also about developing a practice from the collection of aspirations and discoveries ” 9 .

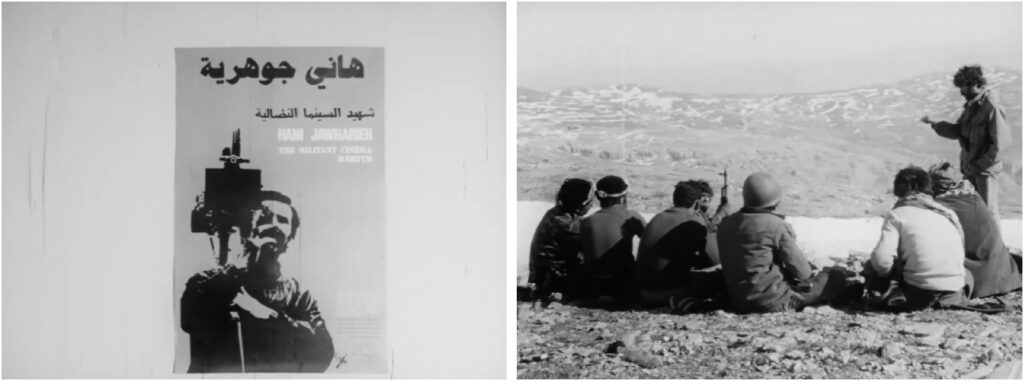

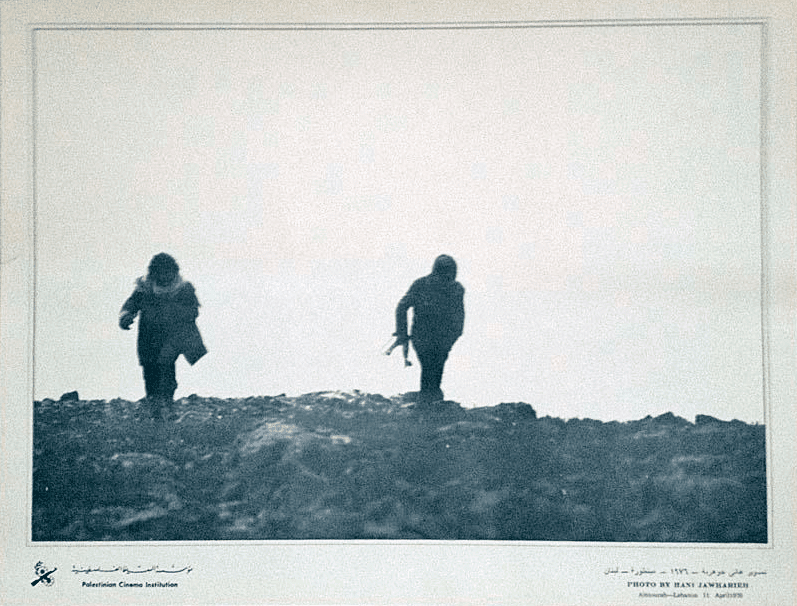

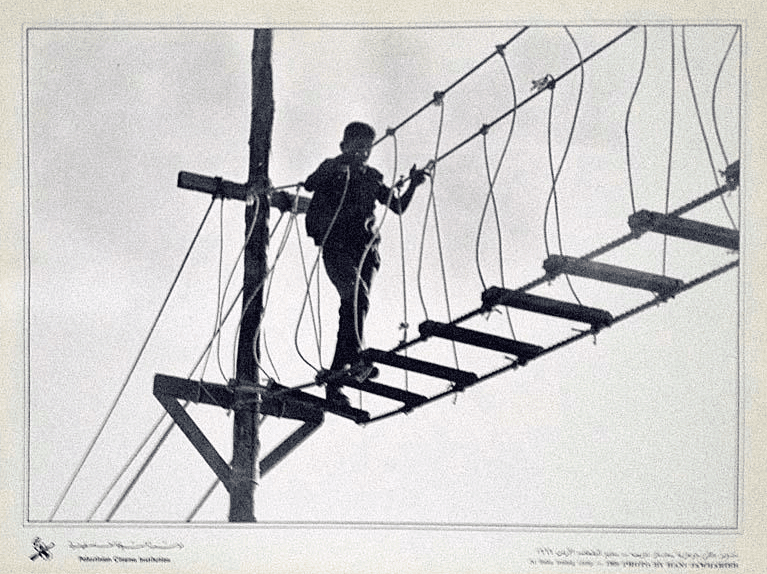

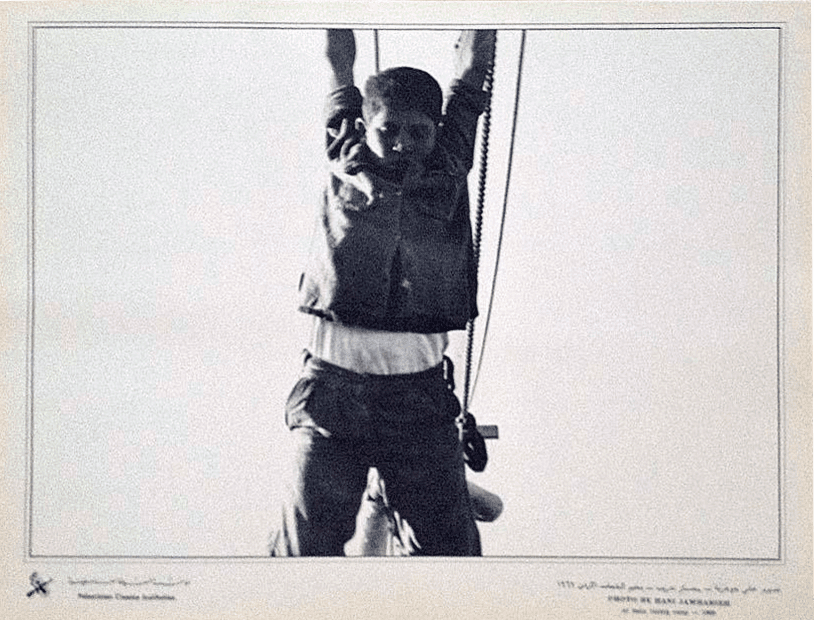

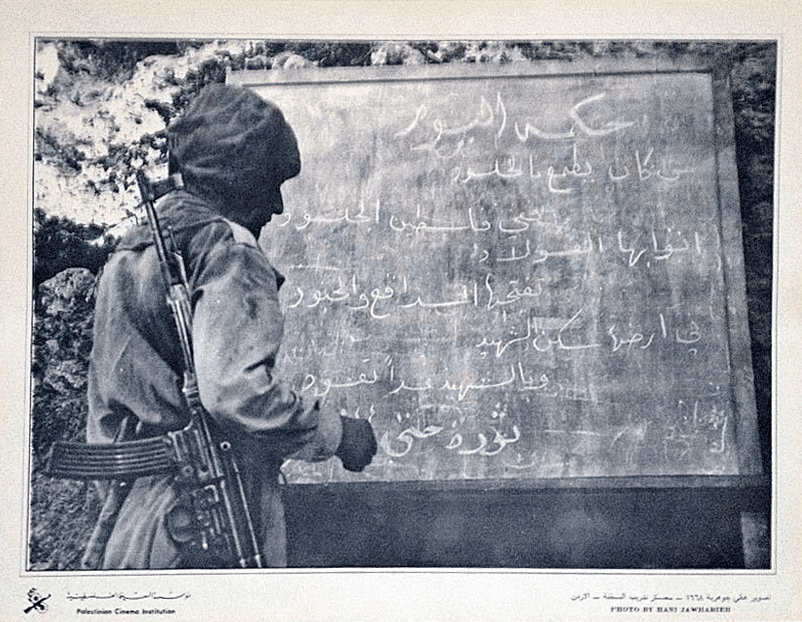

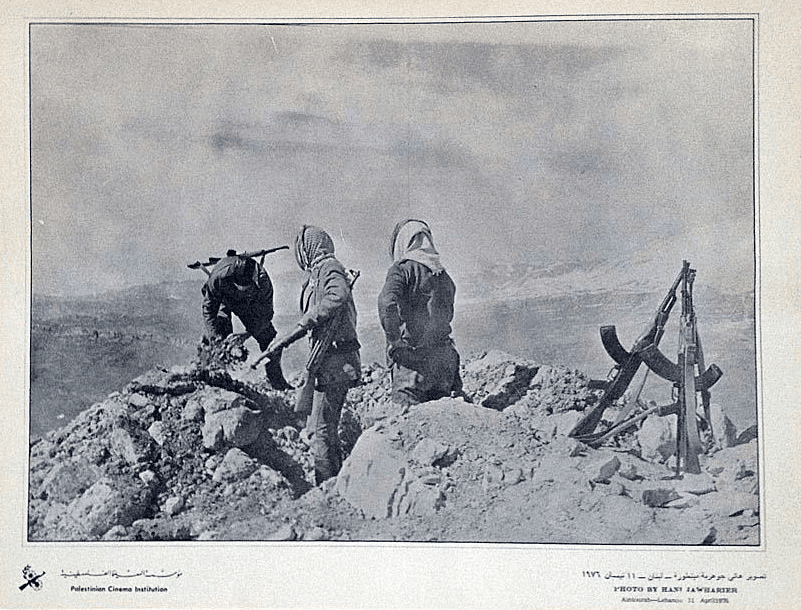

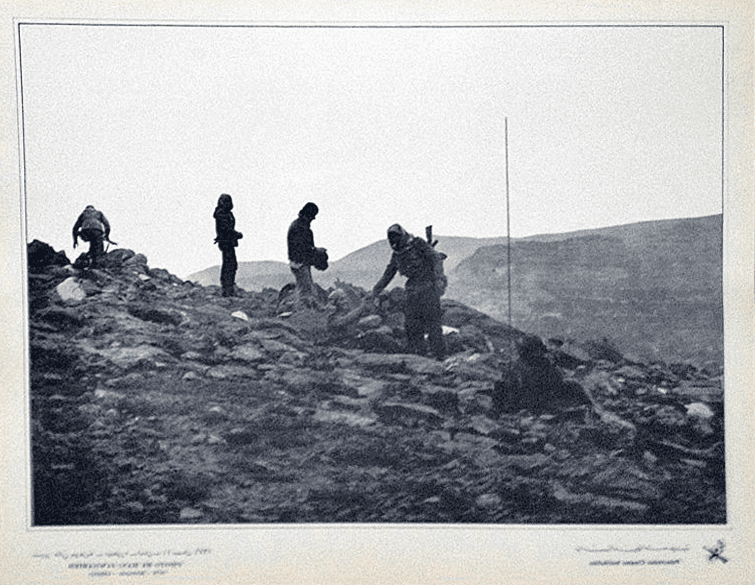

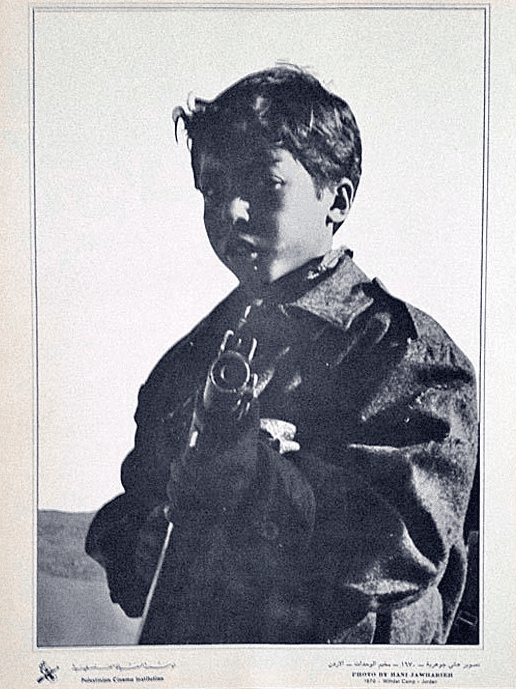

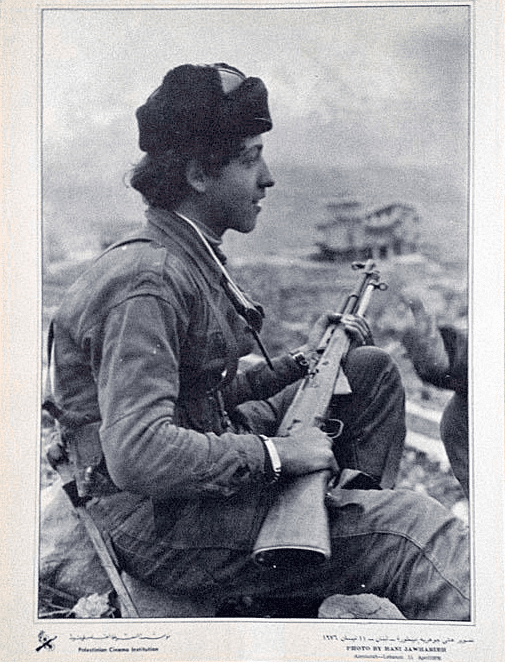

The seriousness with which revolutionary filmmakers brought the cause expressed above all in the falls in combat of many of them. During the recordings of “Soul, Blood”, on the field during the events of the 1970 Black September in Jordan, Sulafa Jadallah was hit by a bullet in the head, which left her partially paralyzed and unable to return to the cameras. Photographer Hani Jawharieh fell into combat in 1976 while recording images of Palestinian resistance in the hills of Antoira, Lebanon - Hani died with his camera in hand, and according to Mustafa, "his camera was also martyred" 10 . In memory of Hani, ICP produced the short “ Palestine in the eye “, Which also serves as a demonstration of the functioning and values of that movement of filmmakers. Hani's latest records were published by ICP in a collection entitled “Palestinian Images”.

This ideological, political and organic binding of filmmakers with the fronts of combat of the Palestinian Revolution is expressed in the speech of the Palestinian delegation to the Tashkent African and Asian Festival in 1973 11 :

The Popular War was what gave to the Palestinian revolutionary cinema its characteristics and its way of functioning (…)

The light weapon is the main weapon of the popular war and, likewise, the 16mm light camera is the most appropriate weapon for the people's cinema. The success of a film is measured by the same criteria used to measure the success of a military operation. [The film and the military operation] both aspire to a political cause (…)

The desire to fight is the most important element in the popular war and, therefore, is also the most important component of film effort (…)

The revolutionary film is dedicated to the tactical objectives of the revolution and also to its strategic objectives. A militant movie, therefore, must become an essential commodity for the pasta, as well as a slice of bread.

And not only should filmmakers become combatants. The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (FPLP), by claiming to recognize the importance of cinema and the need to “absorb more deeply, definitively and firmly the Leninist assessment of cinema (…) as a means of provoking awakening and resurgence ”, He also understood that it is necessary to“ train combatants to record movies and forge pictures that can use the camera side by side with the rifle in the struggle for liberation ” 12 .

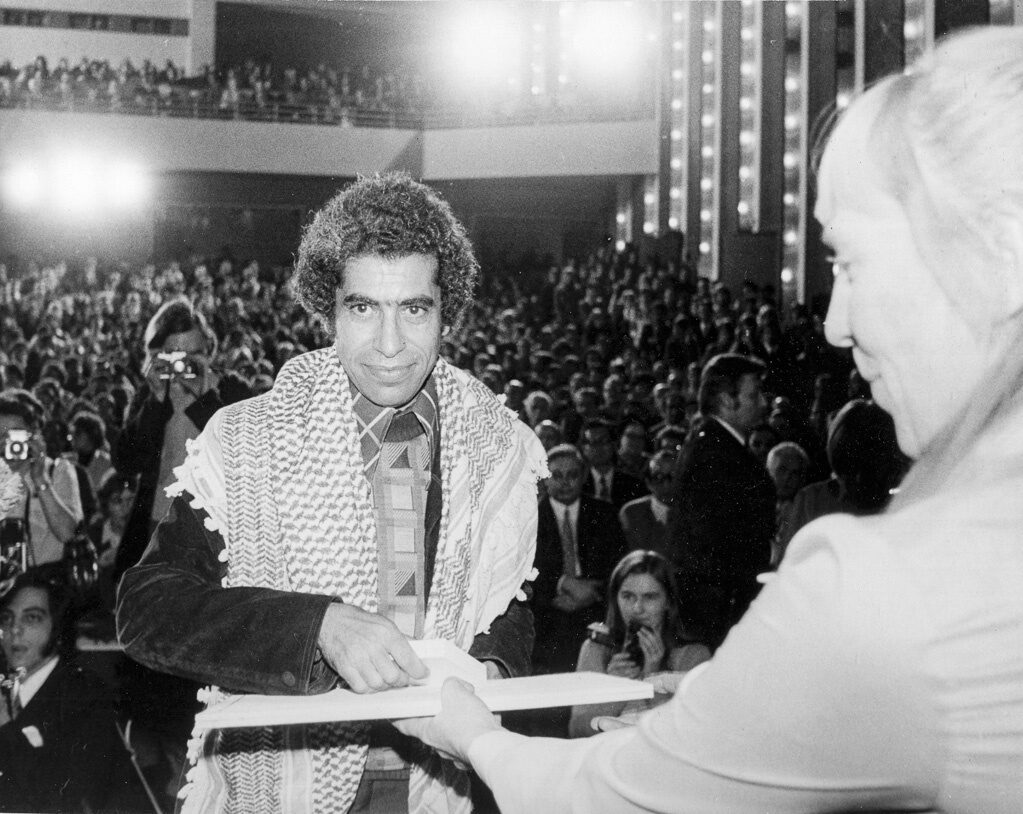

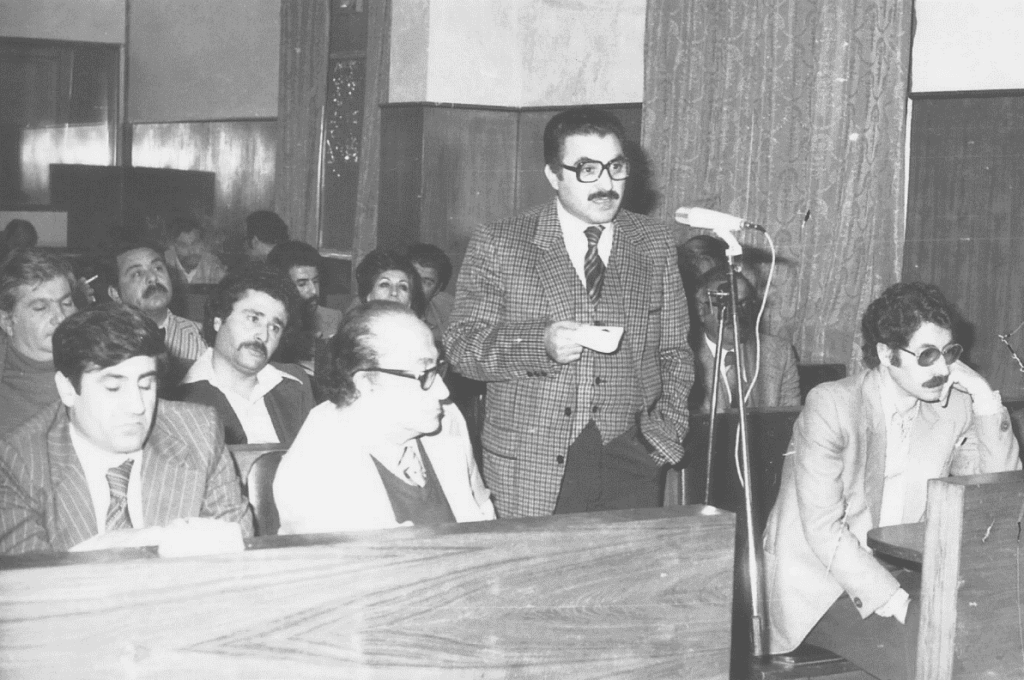

Thus, the various Palestinian resistance organizations also began to look at this: in the mid -1970s, in addition to the ICP, the PLO Culture and Arts Section were already operating on the Audiovisual Front, the Democratic Front for Liberation Committee Palestine (FDLP)-Noteworthy by Lebanese director Rafiq Hajjar-and the FPLP Information Commission-noting Iraqi director Kassem Hawal. FPLP, above all, developed a robust performance and, in about 1975, already organized shows, exhibitions and film courses in guerrilla bases, workers and cultural clubs; published on cinema in the cultural section of Al Hadaf magazine; besides, of course, to sign the production of films like “ Our small houses ”(Kassem Hawal, 1973), who already circulated internationally.

Low tide

Palestinian militant cinema continued to develop until 1982. An important factor was the establishment, after all, of the great ICP file in Beirut in 1974. Under the direction of Khadijeh Habashneh, the file was open to the various resistance forces use it in their own initiatives. Projects such as the magazine “Image Palestine”, launched in 1978 and edited by Mustafa himself Abu Ali, demonstrate a true effort to integrate filmmakers and resistance artists as much as possible in the construction of Palestinian cinema, as well as the “total” character of the vision on the that would be this cinema.

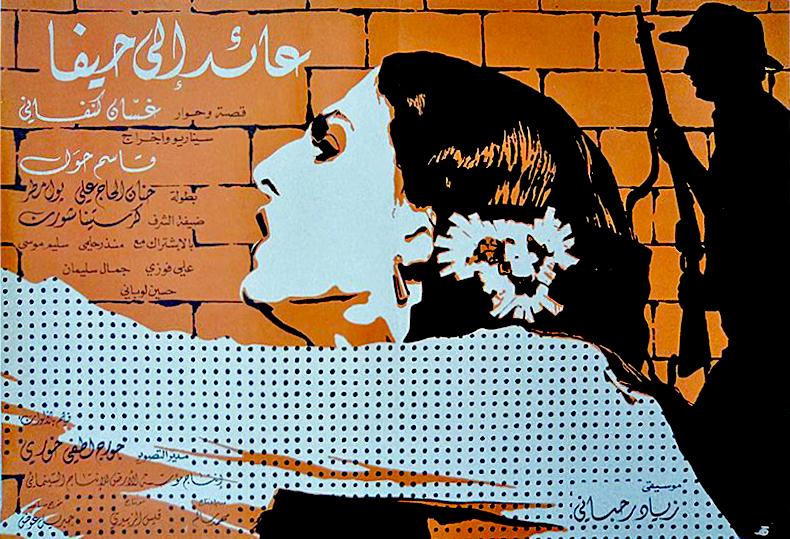

ICP production, above all, the documentary “ Tall el Zatar ”(Mustafa Abu Ali, Jean Khalil called and Pino Adriano, 1977), co -production with the Italian Communist Party, recording the Tall El Zatar refugee field, which was destroyed during the Lebanese civil war. The film was considered lost until it was found in Italy by Khadijeh. Another high point was the realization of “ Return to Haifa ”(KASSEM HAWAL, 1982), considered the first feature film of Palestinian fiction: it is an adaptation of Ghassan Kanafani's namesake novel, with the soundtrack of the famous Lebanese composer Ziad Rahbani. The work was fully funded by the collection and mobilization of thousands of volunteers from the FPLP bases in refugee camps to act as extras and provide resources, food, costumes, locations, logistics, etc… however, when launched more or less in the same period From the siege of Beirut, the film did not get the desired return.

Just as the beginning of this process corresponded directly to the high tide of the Palestinian Revolution, the low tide, which begins with the siege of Beirut in 1982 and culminates with the recognition of the Palestinian authority, also corresponded to its end. On the one hand, Beirut's siege destroyed almost the entire ICP file, even with the effort of Mustafa and Khadijeh to safeguard the movies - carrying the maximum they could from the ICP headquarters in hand, during the temporary armies. Mustafa did not make new films and only in 2004 reestablished the Palestinian cinema group - like a video library - in Ramallah.

The disastrous withdrawal of Lebanon's ULP dispersed filmmakers through the Arab territory once again. Although the individual efforts of artists involved with this period did not cease, the impulse for collective and systematic work was dissipating and slowly gave rise to another Palestinian cinema, whether independent or linked to the state structures of the West Bank and Israel,, carried out by filmmakers who never had access to the works of the militant cinema 13 . On this further development, the consideration that there is enough material for the publication of another article is sufficient.

In the portrayed period, from just over a decade, Palestine emerged a cinema made by the need to do, built in aesthetics and purpose in and for war, by filmmakers and masses creatively mobilized in the same direction - in Khadijeh's words: “ The first film unit to accompany a national liberation movement since its inception. ” As a way of drawing attention to this important piece of the history of militant cinema, as well as to stimulate debates around the role and paths of cinema in today's struggles, we attached texts of the time, used in the construction of this article 14 ; which will certainly give a good overview of the rich artistic process that directly corresponded to one of the auges of the revolutionary storm in Palestine and the world during the 1970s.

Attachments

1. Manifesto of the Palestinian Film Unit, 1972

"Militant cinema"

Militant cinema is one that expresses popular struggle and conveys its militant experiences to the world. This benefits the people themselves and all militant movements around the world.

The Palestinian struggle materializes a new reality with new characteristics that are emphasized in all aspects of Palestinian life. Through this reality, a new Palestinian art is crystallizing through artistic specializations, including poetry, narration, fine arts, music and theater. It also materializes in the cinema.

Palestinian cinema, which is necessarily a militant cinema, is still in the early stages of its development. However, the least that can be said is that it has taken steps in the right direction to turn the film into a gun added to the Palestinian revolution and revolutionary movements around the world.

The nascent Palestinian cinema is aware, at least in the representation of those who work under the name of “Palestinian Film Unit”, who must express the spirit of the people's armed struggle, criticize the corrupt and delayed reality and plant the values of the popular war of release. This culminates in the right to the self -determination of the Palestinian people in their lands.

Palestinian militant cinema must find new tools and structures capable of capturing the glorious struggle of the Palestinian people. Popular cinema must express the popular war.

Militant cinema has specific values and standards that differ from traditional cinema. As such, values and standards should not be confused.

The value of a militant film is measured by its benefit to the revolutionary cause that the film represents. Palestinian militant cinema does not represent a geographical affiliation, but a sonship with the Palestinian revolutionary cause.

Long live the struggle of the people for liberation!

Long live the armed struggle!

Long live the militant revolution!

2. Manifesto of the Palestinian Film Group, 1973

Arab cinema has long been delighted to deal with issues that have no connection with reality or deal with it superficially. Based on stereotypes, this approach has created habitable habits among Arab viewers, for whom cinema has become a kind of opium. He pushed the public out of real problems, overshadowing his lucidity and conscience. At times throughout the history of Arab cinema, of course, there have been serious attempts to express the reality of our world and their problem, but they were quickly suffocated by the supporters of the reaction, who fought fiercely against any emergency of a new cinema.

Although recognizing the legitimate concern these attempts had, it should, however, be clear that, in terms of content, they were usually underdrew and, at a formal level, always inadequate. It seems that one could never escape the heavy heritage of conventional cinema.

The June 67 defeat, however, was a shocking experience and raised some fundamental issues. Finally, young talents committed to creating a completely new cinema in the Arab world, convinced filmmakers that a complete change should affect both form and content have also appeared.

These new films raise questions about the reasons for our defeat and take courageous positions in favor of resistance. It is important, in fact, to develop a Palestinian cinema capable of supporting with dignity the struggle of our people, revealing the facts of our situation and describing the stages of the Arab and Palestine struggle for the liberation of our land. The cinema we aspire will have to devote to expressing the present, as well as the past and the future. Your unified vigor will result in the regrouping of individual efforts: in fact, personal initiatives - whatever their value - are condemned to remain inappropriate and ineffective.

It is for this purpose that we men of film and literature have distributed this manifesto and asked for the creation of a Palestinian Film Association. We attribute to it six tasks:

- Producing Palestinian films about the Palestinian cause and its goals, films that originate within an Arab context and are inspired by democratic and progressive content.

- Work for the emergence of a new aesthetics that replace the old one, capable of consistently expressing new content.

- Put all the cinema in the service of the Palestinian Revolution and the Arab cause.

- Design films intended to present the Palestinian cause to the whole world.

- Create a file of films that will bring together film and photographic material about the struggle of the Palestinian people to enable the reconstruction of the historical steps of their struggle.

- Strengthen relations with revolutionary and progressive film groups around the world, participate in film festivals on behalf of Palestine and facilitate the work of all friends groups who work to achieve the objectives of the Palestinian Revolution.

The Palestinian Film Association is considered an integral part of the Palestinian Revolution institutions. Your financing will be ensured by the Arab and Palestinian organizations that share with your guidance. Your office will be at the Research Center of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).

3. “Cinema and Revolution”, FPLP, about 1975

Although monopolistic companies have dominated the art of cinema in their production and distribution and imposed their capitalist thinking in the content of the films produced, Vanguard artists have been struggling to take advantage of the use of this environment for the benefit of the proletariat, their thinking and their future. The attempts of world Zionism since 1897 in exploring the use of cinema and its ability to influence the broader masses can no longer continue, in their domination, just as before, due to the defeats that imperialism received from the hands of peoples in Fight in the world.

With the Palestinian resistance movement, the techniques of film production were developed, which recorded the reality of the revolution. However, in their early days, they did not go beyond the recording of some documentation, without moving to a broader scope, in vision and obscurity. Perhaps the initiative of the Popular Liberation Front of Palestine, from 1970, played an important role in this field, when it began to produce documentaries, in view of the ability of these films to express the revolution and their thinking and to be a linked base to reality in a material way. This activity occurred at several levels:

- Permanent exhibitions on Fedayins and Palestinian refugee fields;

- Film shows in organizations and cultural clubs and working areas;

- Greater attention to film festivals, to consolidate relationships: on the one hand, for the frequent participation of Palestinian cinema and progressive international cinema, on the other, the possibility of Palestinian resistance, in particular the Popular Front, to show the true facts of Palestinian struggle and the implications of the Palestinian cause. Thus, he exposed the essence of Zionist forgery and portrayed the closest image of the truth about the Palestinian cause, raising the voice of the Palestinian cause for the first time through the Leipzig Festival in 1971. After that, Palestinian cinema went through many festivals, us What is the relationship between Palestinian revolutionary cinema and world cinema was strengthened, so that it unified in the same line of exposing the fascist methods of colonialists and invaders, and portray the continuous struggles and victories of peoples;

- Distribution of Palestinian films to political parties and student and workers' organizations around the world. The role of these films was very important, both to incorporate the thought, strategy and continuous struggle of the revolution, and to refute the allegations of Zionism and its exploiting and fascist way of thinking.

- Preserve the cinematic and photographic documentation of the Palestinian Revolution in a special archive, as a source material not only for Palestinian filmmakers, but also for friends who want to participate in the revolution through Palestinian films.

- Train the combatants to record movies and forge frames that can use the camera side by side with the rifle in the fight for liberation.

In addition to this cinematic work, the activity included another side in the field of cinema culture, creating human consciousness, in order to highlight the value of revolutionary cinema and the role of cinema in the march of the revolution, and, from the experiences of cinema in The whole world, clarify its role in the struggle against imperialism, monopoly and the values of capitalist thinking, through the art of making cinema.

This was through the cultural section of the goal , the main magazine that speaks in the name of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, as well as through courses and lectures organized by the Front Artistic Committee. Aware of the importance of this vehicle of culture, FPLP is striving to develop this aspect through continuous productions and exhibitions, as well as the consolidation of ties with all filmmakers in the world that strive to expose all types of domination and exploitation, in order to break the monopolistic strangulation that is applied by the world capitalist companies.

Palestinian cinema has played an active and effective role during its short life and within the limitations of its activity. After the cinema has long been absent from participation in the course of events, now the Palestinian films have been a new and growing phenomenon within the broader phenomenon that is armed, linked to it and expressing it of a phenomenon that is a phenomenon. form or another. Although the total sum of Palestinian film activity remained confined to some initiatives and below the proper planning and programming standards, it has made a long leap. There is no doubt that the criterion for the development of Palestinian cinema lies in the maturation of political and cultural conscience about the importance of cinema, to absorb more deeply and firmly the Leninist assessment of cinema, not just as an admiration and East to the potential importance that the teacher of the proletariat has seen in the cinema as a means of provoking the awakening and resurgence (of all the arts, considered the cinema the most important). We will work with all our efforts and capabilities to direct these words, so that Palestine's combatant cinema can advance to the first ranks within the world film movement.

4. Excerpt from “The Experience of Palestinian Cinema” by Hassan Abu Ghanima and Mustafa Abu Ali, 1975

(…) From the outset, unity members were quite clear that they were working within the structure of a prolonged popular war, an armed revolution, and that they would have to define the particular nature and specific circumstances of their activity so that they could respond correctly to the needs of the people and avoid causing them any harm. The unit had 3 members: two (Hani Jawharieh and Mustafa Abu there) had studied cinema in London; The third - a comrade (Sulfa Jadallah) - had studied in Cairo. They immediately asked if artistic standards studied were corresponding to Palestinian aspirations at a time when the armed struggle was beginning to develop. Should they speak to their audience with London or Cairo -learned shapes or should be seeking to develop an original style capable of playing the Palestinian and Arabs masses? Even more: could they express our armed revolution in foreign forms? Should they imitate invented and used styles by film language combined with colonialism, or should it create and develop new modes of expression - a new cinematic language linked to Arab heritage in general and particular Palestinian resistance?

This was the important question that marked the nature and work of the unit group since its origin. It was clear from the beginning that the way would be long and difficult and that it would also lead us to evolve. The question was to find the way through which popular cinema could express the popular war.

The experience with the movie “With Soul, With Blood”

The answer to this question was given to us by doing “with soul, with blood” by Mustafa Abu Ali. During the events of September 1970 in Jordan, the unit was able to film several sequences in synchronized sound. Adding to other scenes that had been filmed earlier, we had special material to advance and test our ideas about militant cinema. Unfortunately, after September 1970, all the unit's work rested on the shoulders of only one of its three members: Sulafa Jadallah was hit by a bullet, which left her partially paralyzed, and Hany Jawharieh was isolated by the siege and unable to regroup. Mustafa Abu Ali felt the need to offer a political analysis of events in Jordan and was asked to restrict her work to the sequences already recorded. It was only after several discussions that he agreed on the need to gather the sequences, based on a thorough political analysis.

The question, therefore, was no longer to make a documentary, but to make a militant movie. For us, the difference between the two lies in the fact that a militant film uses documentary recording and other materials as the basis for formulating an elaborate political statement, while a documentary is generally limited to the simple juxtaposition of documents. Thus, political analysis became the main axis of filmic work, in a sense replacing the scenario itself. The analysis was developed with the participation of the maximum resistance frames the possible, with the director restricting themselves to translating it into technical and material terms. The interaction between the political and cinematic element lasted for four months, during which various editing styles were tested, usually based on two rhythms - fast and slow - particularly during the first sequence, where illustrations were used to better illustrate the content . Each editing rhythm was tested on exhibitions in the refugee camps, and it was in this way that we decided to abandon the fast pace. This also led to the decision to abandon the illustrations and replace them with instructive scribbles made by children. The author thought that the scribble would be closer to the real conditions than the illustrations and most easily understood by our audience.

But following this, after several consultations with the people, the unit decided to abandon the symbolic style of the beginning of the film.

Popular consultations

Among the various consultations made by the unit, one was considered particularly interesting to grasp the reactions of the Palestinian people. These consultations, which were made in the refugee camps, in the guerrilla bases, and in advanced schools, concern the reception of films made by the unit, movies of foreign friends about Palestine and illustrative films of the action of national liberation movements around world. The unit raised a series of questions and distributed them to viewers before the screenings. The answers either were delivered back directly before the exhibitions, during another projection or sent back later, by any appropriate means. After a while, we met a pile of documentation and important information, most of them coming from Palestinians in Lebanon or Syria. All screenings included, among other films, "with soul, with blood."

Six impressions were inevitable:

- The warm reception and applause that films have confirmed the concern that our people have in their primary interest: the revolution.

- This concern proves the significance of cinema as a popular environment and underlines the need for the filmmaker to have a strong political awareness.

- Reactions to Vietnamese, Algerian and Cuban movies, and in general any movie that concerns armed struggle are no different from the reactions to Palestinian films. This confirms that our people are aware that their fight against Zionism clearly fits the most general context of international struggle against imperialism.

- Spectators prefer realism to all other artistic styles.

- Spectators used to commercial films tend to manifest defeatism in their reactions to certain films, most notably about "with soul, with blood," which surprise them. Because they are not familiar with militant cinema, they become unable to form a clear opinion. However, discussions and reexivities help to clarify them.

- The insistence with which the people ask for more exhibitions clearly demonstrate their need to discuss their concerns and discover the struggles of other peoples. Unit members have firmly convinced that whatever the question should be transmitted to the masses, as they are the main interested parties.

In addition, the unit met with all foreign filmmakers who came to film or report Palestinian resistance, promoting discussions that were very fruitful in terms of the evolution of ideas about militant cinema in the Middle East and worldwide. The unit also won a lot when contacting progressive filmmakers at various international festivals.

Conclusions

The unit has made several conclusions of its experiences:

- Militant cinema is a new experience in the filmic world. It is observed that he really developed with the armed and popular revolutions in Vietnam, Cuba, Algeria and Palestine. It also emerges in the fighting of Latin America, and with struggles in North America and Europe, where collectives make films denouncing imperialism and celebrating popular resistance. It is from the popular war that our militant cinema takes the patterns of their work, as well as their inspiration.

- The militant film collective must, in our view, perform all the operations from the writing of the argument to the projection of the film. At each step, a cell, strategic and tactically involved with the problem with which the film is leaning should be considered.

- The production of a militant film has a double nature, as its authors must have two factors in mind: provisional tactics and long-term strategy in the fight. In any event, the militant movie should be "useful as bread and not superfluous as a perfume."

- Militant work in cinema cannot achieve its purpose without projection of the film before the masses involved in the struggle in question. The filmmaker should therefore move to present his film himself, whether open or clandestine exhibitions, depending on the stage or nature of the fight. The relationships between the filmmaker and the masses must be continuous, pervading all the stages of the film's making.

- Finally, militant cinema must have a number of qualities. It must have truly revolutionary content; a serious approach; take into account the actual reception of the hearing to those who go; and be able to counteract the cinema that comes from the imperialist world.

5. Excerpt from “For a Revolutionary Arab Cinema”, an interview with the film magazine with the Palestinian film institution, 1975

Film that responds to the immediate needs of the current situation or may be a movie that meets a more long -range strategy. But in both cases the criterion must be its usefulness.

From another point of view, revolutionary cinema must meet four requirements:

- The justity of inspiration-the filmmaker must obey revolutionary ideology and devote himself to put it into practice.

- The subject must be treated seriously-to this end, one should end the traditional methods of Hollywood cinema and replace them with methods adapted to the needs of the fighting people in order to express their hopes and aspirations as accurately as possible as possible as possible .

- The message must be transmitted correctly - language must be simple, clear aesthetics; Cinematographic extravagance and stylistic pyrotechnics need to be refused. Generally, complications should be avoided and fighting for clarity so that the masses understand the revolutionary content of the film. It is necessary to closely examine the question of the relationship between the film and the masses, starting from the very conception that people have from cinema so that they can transform it. Currently… cinema in its entirety has a negative influence. Why? Because it is considered as a hobby, even an opium, a drug. Only with the correspondence between the masses and the filmmakers will a new conception of cinema be established.

- The mission of revolutionary cinema must be, above all, to deal with local and more crucial problems, dealing with living reality in all its dimensions - political, social, economic and cultural. The description of this reality must also unravel the deep and fundamental causes of the evils that the people suffer and to define and clearly condemn those responsible. Finally, you need to exhort the masses to change what doesn't work.

In this perspective, revolutionary filmmakers, who are they, should not forget that the main target must be military, economic and cultural imperialism that enslaves and loots Africa, Asia and Latin America. Ignorance, poverty and underdevelopment of these areas have their origins in the policy of imperialism.

Needless to say that we are looking for contacts with all foreign friends to discuss these problems and, together, define a new type of cinema in all countries in the world, but especially in the Third World, which needs to break free from enslavement cultural of Western imperialism. We want a popular cinema where the people are in the process of making history.

6. “Palestinian images”, latest photographs by Hani Jawharieh, 1978

This text expresses the author's opinion.

Grades:

- Remembered by Khadijeh Habashneh from a meeting between the Cuban director and Palestinian Mustafa Abu there at a film festival in Algeria (taken from Electronic Intifada ) ↩︎

- Taken from Palestine Film e Electronic Intifada . Nessa Another article Jacir comments on his work. ↩︎

- Attributed to Mustafa Abu there in a 10 -year memorial of your death , prepared by filmmaker Khadijeh Habashneh. ↩︎

- Taken from “The Experience of Palestinian Cinema” by Hassan Abu Ghanima and Mustafa Abu there. ↩︎

- In Kay Dickinson's Arab Film and Video Manifestos (2018): “Upon probing viewers, the fact that these populations that had motivated cinema in the first place was honored; The movies were for them . The filmmaker was just an equal taxpayer, employing his own private talents to promote the major goals of liberation, the authorial voice subordinate to the biggest cause. ” ↩︎

- Taken from “The Experience of Palestinian Cinema” by Hassan Abu Ghanima and Mustafa Abu there. ↩︎

- Idem ↩︎

- Interview with the Palestinian Film Association, taken from the ed. 52 Merip Reports Journal . ↩︎

- Taken from the book Arab Film and Video Manifestos (2018), by Kay Dickinson. ↩︎

- Taken from the book “ Knights of Cinema: The Story of the Palestine Film Unit ((2019), Dr. Khadija Habshah. ↩︎

- The quote, incomplete, is present in the book “ Palestinian Cinema: Landscape,Trauma and Memory ”, de Nurith Gertz and George Khleifi. ↩︎

- FPLP's “The Cinema and the Revolution”, about 1975. ↩︎

- A full description of this process is contained in the book “ Palestinian Cinema in the Days of the Revolution ”(2018), by Nadia Yaqub. ↩︎

- The first attached text was taken from the book “Knights of Cinema: The Story of the Palestine Film Unit” (2019), by Khadijeh Habashneh; The second and third text were taken from the book Arab Film and Video Manifestos (2018), by Kay Dickinson; The third, from volume 2 of “Communication and Class Struggle”, organized by Armand Mattelart and Seth Siegelaub (1983) and Ed's fourth. 52 of Merip Reports magazine. Unofficial translations made by the author of the article. ↩︎

We also leave here the link From a file produced by the Palestinian cinema index, where you can access the movies and books mentioned, and so many more.