1

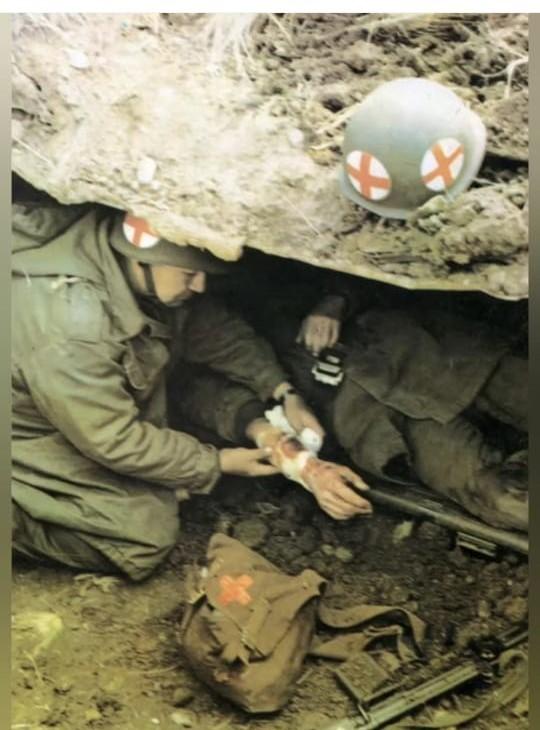

In the photograph above we see four of the six civil surgical instructors who, as volunteers, rushed to the Falkland islands to join the health team that worked at a frantic and incessant rhythm at the Puerto Argentino Military Hospital. However, if the high time in the early days of that June 1982 had made the presence of specialized professionals essential during the stages of the surgical procedure that had become more and more diverse and complex; on the other hand, the intensity of the battles, the ammunition tracers Side by side and the growing stage of the explosions made it impossible to land the six young women in the island territory - they remained aboard the Ara Almirante hospital ship Irar that was attracted to Bahía Groussac, in the line of fire, in front of Puerto Argentino .

Of course, Irizar complied with all the requirements defined by the Geneva Convention of August 1949: the white -painted hull; Several red crosses scattered in visible places; the speedboats adapted for the transport of injuries; the helicopters for their air transfer was also painted white and with the red cross; the evacuation of any and all onboard weapons, ammunition or explosive 1 . However, the reports Girls Newly come to the theater of operations of a war that extended by land, sea and air evoke the tension and gravity of what was living. According to Jorge Muñoz, Maria Marta Lemme described her wonder when she realized that a large part of the fired projectiles passed boiling nearby 2 . Silvia Barrera told us that at dawn on June 14, where numerous surgeries had been performed, a group of camouflaged English, near the hospital ship, wanted to attack an Argentine troop on the beach. The crew of Irizar, breaking with the awake in Geneva, lit one of the giant reflectors and warned the detachment of Argentines that they were for being attacked.

Ourselves from Silvia Barrera:

It was a widespread shooting between the English and the Argentines who were on the beach, and on this day there were people from the irreat who also shot. This has made the rules of the Geneva Council on both sides break. By the time this was happening, we didn't realize, we were in a series of surgical procedures. And in thinking that the irzazing was one of the targets of the shooting… If any projectile reached the oxygen tubes we had to go through the air. 3

2

On a rainy morning of the autumn Portene, Silvia Barrera offered to receive me for an interview with me a little of her condition as a veteran of Falklands. Silvia suggested to me the place: the internal facilities of the Central Military Hospital of Buenos Aires where 41 years still works from that already distant year 1982.

I had contacted it by whatsapp And I asked you to take some photographs and documents from your personal file - so I could illustrate the article. Silvia said she didn't worry about this. He said he has been visiting several primary and secondary schools for years to explain to students what the Falkland islands and the other South Atlantic Islands were; What is its strategic importance from a historical, economic and geopolitical perspective; its natural riches, oil; the proximity of Antarctica and the Strait of Magalhães, the only place of passage to the Pacific; Silvia tells them what was and how the war came; the work without rest of the health team; the bravery and disaste of those who fought for the sovereignty of a territory that had been claimed in the main international forums within the limits of diplomatic actions for decades; And by his tireless work of social and collective memory, Silvia reinforced me, had a material already prepared to introduce me. It is that, according to her, in her student time what was learned at school was only that the Falklands were Argentine, who were located in the South Atlantic, that the English had usurped them to the Argentines and that one day the islands would pass to be national territory. No more than that.

In other words, Silvia says that when asked if she would accept to collaborate in the health team in that principle of June 1982, it was for these evil, epic and distant, that she offered to go.

Says Silvia:

The petition arrives at the Central Military Hospital on June 7. They gathered all in a room and wonders which of us would accept to go to Falklands. Those who were married and had children said no. And we have been five of us. As the request was 10 instrumentalrs, the petition is referred to the Military Hospital of Campo de Mayo, and one more willing to go. Everything was absolutely new to us, including us. The oldest was 23 years old. All skinny and with the hair to the shoulders at least. We only had summer clothes to take - that's what they gave us. There were no winter clothes in the hospital. Imagine that it was not any winter, but the patagonian winter. We were all civilians without any military instruction. At that time, neither were military women. The clothes that handed us were men's clothes, two numbers above ours. We have not received helmets. We had to bend our sleeve to work. It was all new and improvised. What's more, it was all urgent for yesterday. Aware that on June 7th, we got it right. On the 8th, at four o'clock in the morning, we took the flight towards Río Gallegos. Without any documentation. When we got there, no one was waiting for us. It was in a war. The call message that had left Puerto Argentino to Buenos Aires, days before, had been short, straightforward and objective: we need instrumentalrs. The response from Buenos Aires to Puerto Argentino was equally direct: we sent six. 4

And the amazement doesn't stop there. At the journey to Irhzar from Buenos Aires, Susana Maza, Silvia Barrera, María Marta Lemme, Norma Navarro, María Cecilia Richieri and María Angelica Sendes would enter, take off, fly, land and leave an Aerolíneas Argentine plane; They would do some of the route already in Río Gallegos in a jeep without hood, then in a truck and finally rose for the first time in his life in a helicopter. And then the landing on the hospital ship. All entirely new, adrenaline in the heights, but despite that Silvia Barrera states that We knew that the only women living such a thing would be us, and that was tremendous to us! When the helicopter landed on the irzar and unlocked the doors and we went down, it was a general shock. Until then no one had seen women dressed in the military uniform 5 .

3

It was still June 8, 1982 when the work of girls it started. They were distributed in different sectors: Silvia Barrera was crowded in the intensive care and general surgery sectors; Susana Maza in the screening of injuries and cardiovascular surgery; María Marta in General Surgery; Norma Navarro and Cecilia Richieri in traumatology and, finally, María Angelica was concerned with the ophthalmology sector. New injuries arrived at all times, and they were not patients such as they were used to watching at the Central Military Hospital in Buenos Aires. They were wounded that came from the battlefield of a war that advanced toward their ragters. During the interview, Silvia Barrera seemed to make a chronology of the stages of war from the typology of injuries and medical occurrences.

In its terms:

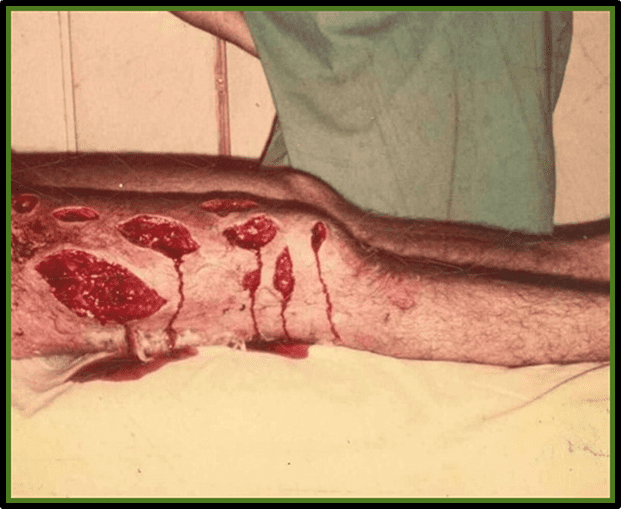

(…) Another type of wounded Puerto Hospital are beginning to arrive: the patient with multiple injuries, pump fragments, firearm wounded, are injured with a degree of complexity in growing after a whole month in the whole month Falkland conditions. And then they begin to arrive soldiers with a trench foot, with immersion, with a trench hand, and start to arrive in large quantities. (…) In the specific case of the trench foot, the member becomes black, cutting the circulation, is the freezing of the foot of the combatant that remained sometimes a whole week inside the trenches. Depending on the stage, it is possible to reverse this with anticoagulant medications, with the hyperbaric chambers. Irízar had this equipment. It was an antarctic ship. But if you could not reverse the picture in a day or two, if you had to do the amputation. About five trench foot amputations were made at Irízar. 6

Let us go a little about the specific cut that meets Silvia Barrera's report, and here we evidence the testimony of a recruit [ colier ] who suffered from the hardships described by our instrumental in the battlefield itself. This is Daniel Cepeda, born in Villa María, in Cordoba. Cepeda was incorporated in February 1982 and boarded March 26 on the ship Cabo San Antonio under the orders of the Warrant Oscar Reyes. It is in the first wave of combatants that will arrive in the Falklands. Cepeda had both feet amputated by freezing. He suffered from the indescribable hardships of the trench foot. If your report invokes the borderfish condition of pain, at no time is it self -industry or loaded from the victim inks. It is important to note that, upon returning from the War Operations Theater, he did not immediately lowered as a certain contingent of recruits, Daniel Cepeda remained hospitalized at the Central Military Hospital until November 1982. Case similar to his is his partner Regiment, the recruit Carlos Moyano, born in Arias, another city of Cordoba. Moyano also suffered amputations on both feet, also by freezing. Remained hospitalized at the Central Military Hospital until his full rehabilitation in 1985. Daniel Cepeda and Carlos Moyano received the military distinction in the form of the medal The Argentine army to the injured in combat.

Let's look at the testimony of soldier Daniel Cepeda:

Near this bluff there was a house, like two kilometers. There we got some quilts, one covered, five or six covered for eleven. My feet were already very swollen and I had to stay there for two days. I couldn't walk, I hit my head against the wall of such pain. They made a kind of stretcher and took me. Reyes made us stop: "Please, I ask you, you can't give you, you have to walk." And I wanted to kill him because I couldn't stand the pain, but he was right, then I could recognize the effort he made to carry on us, to motivate us. I remember the first time we set up a fire, he put his feet near the fire, warmed and cried two nights in a row of pain. I asked us to do the same. If we had done just like him, we might cry two days as well, but we would have ridden ourselves. But it was the fate of each of us. 7

To which Carlos Moyano adds:

The house was abandoned. The only thing we found was a little sugar and flour, and there were some horses. The warrant officer told us to see if we could get some to follow and arrive faster, but they were very rods. Cepeda felt a lot of pain. He took his socks to make a kind of tourniquet and when he wanted to put on his boots again. Neither he nor the Godoy cable could follow. The last to fall was me. When I took the boots it was worse. (…) Just that day I say: “I will try to go out and make signs with the cover”. Because every moment the helicopters passed. The cable said to me, "Hold on a little more than someone will appear." And said and done, before ten in the morning reyes appeared with the English . 8

Following this, let us follow what Oscar Reyes, the warrant officer of the 25 Infantry Regiment, from the city of General Sarmiento in Chubut, and a conductor of the regiment in which Carlos Moyano and Daniel Cepeda were, among others. Oscar was 23 when the war began. Participated in Rosary Operation and was moved to Darwin-Goose Green. Subsequently, it was sent to Marco 234 in the Strait San Carlos, where the British troops landed. By its performance received as a distinction to Medal to value in combat.

Listen to what the Oscar Reyes Warrant Officer tells:

They were dying little by little. Godoy no longer wanted to eat, Cepeda and Moyano couldn't get around. In the early hours of the morning I made a weak sun that soon disappeared with the bruked, and I enjoyed this sunshine to get the sick out of the trench. He took his socks so that his feet were airy because they could no longer their boots. The skin becomes yellow, and as soon as there is a pink tone and some stains that then become dark, the sole of the feet becomes hard and turns out to be quite dark. When you will handle it is the gangrene. The boys did not want to surrender, cried and said to me, "Please follow you, leave us here, otherwise they will die eleven instead of three." And so I realized that the best way to help them was to follow the people who were in a position and send the soldier Clot to San Carlos to surrender and request the rescue of the injured. I prepared you, I taught you some phrase in English to ask for help: I'm Soldier… We Need Help…, I left the injured in the highest and so far as possible, I left them food and asked the clot to give me one day of advantage so you could distance the rest of the troop. 9

Silvia Barrera recalls that the English bombarded every night because they knew that the Argentines did not have the equipment needed to overcome the absolute pitch of the patagonian night. Daniel Terzano, another colier Fighting in Falklands states that the effects of brightness and lighting that was displayed came from the use of signs. And the English made continuous use of this resource. According to him, sometimes, after the canes, he listened to the bangs of mortars and cannons. They were like guides for artillery shots, or for troop advances, or announced the lifting of helicopters. 10

When he dawned, in the few hours he lasted the day, the [Camilleros] machines went out to collect the wounded and the dead in combat. Such machiners were 18 -year -old soldiers, chosen to finger. They unfolded from preventing the wounded from uncomposed in pain when they were placed in the stretchers. Silvia draws our attention to the fact that the sale's terrain is stony, with small elevations. Makers countless times, they were forced to run with the wounded in the crossfire of a ongoing war until they arrived at a rescue post where there was a nurse or nursing student who sought to stop the bleeding to prevent bleeding from advancing during the helicopter transfer to the Puerto Argentine hospital. In those days of June, the temperature reached 5 degrees below zero and the winds were absolutely incessant.

Silvia Barrera says that many of these patients were operated already in the hospital of Puerto Argentino, or if it were not possible, if she stabilized them so that she could resist the transfer to the continent. However, certain patients could not stand the height, the pressurization of the Hercules plane, and behold, the process had to be done through helicopters to hospitals. In the Argentine case, it was Bahía Paradise or Irreat.

In the end of the war, the Puerto Argentino hospital collapsed, in the terms of Barrera, and it is then that it completely modifies the diagram of what can be in hospitals. Silvia Barrera tells us the case she experienced with her companions and the entire medical staff on the ship Irízar:

Then we started receiving another type of patient. A patient who is in living flesh, who has to break his clothes, wash it, disinfect him. They are men who haven't bathed for over a month because they were in the trench; And we had to see if there was bleeding, and if there was, where it was bleeding. Of course all this without any anesthesia - because first we had to see where the wound was, if it was just a wound. (…) In the case of Sparks - Wounds caused by explosive fragments, cannot be sutured. Just think what the picture was: the splinters entered your skin and what they entered, they carried the material of the clothing, besides the accumulated dirt, add to that, the earth, the snow, the vegetation, all inside, then, then It had to be taking everything around the wound - which has to remain open so that it is not infected. 11

I ask Silvia if they were sorting patients, and if this first care was something they, like surgical instructors, were used to doing:

It was the doctors who evaluated if such a patient went to the operating room, or if this patient could expect. We didn't have any rest time at Irízar. The ship's staff - the drivers, the crew that was responsible for the most diverse internal services of a ship, all had their work routine. We at health did not have. It was zero of rest, and practically zero of food. About what you asked me, yes, we started to accumulate functions. We were nurses, makeshift psychologists. When I say 'nurses' I am referring to the nearby professional, who takes care directly from the patient, who contains him, who takes his arterial, bloodthirsty measures. They are also those that often do and undo bed, which give food, medication, which help locomotion, care essential with hygiene. We are surgical instructors, our preparation is of another order. The patient, under normal conditions, when he arrives at the operating room is already half slept, has already been sedated with a pre-anesthetic. In general, no one knows who the instrumental is in a operating room. We thought that in Falklands it would be exactly the same as we were used to, and there we met another world. Listening to Homeric Shouts, Ensite Straights, things we never imagined seeing and listening, all of this we saw closely, from inside the scene, as protagonists who welcome the patient who feels that he lost everything, the war, a body part or that is on imminence To lose it, this wounded that has become a decapacitated, who does not even know how to remain alive, who has no idea how to have to touch the life that fits him later. We were the ones who welcomed this combatant. 12

Silvia Barrera tells us that one day Irízar began to move to 45 degrees, lean, and they had a surgical procedure ahead. They had to tie with pieces of cloth the surgeon, the assistant, the instrumenter (who was she) and that it was necessary to move as in a choreography of rehearsed gestures, as in a contradening. It was a complex surgery that lasted all night - because there were multiple wounds, a bullet in one hand, a Sparge In the stomach, and a lot of them in the legs. Everything came out, she says. But it was all absolutely unusual, something that completely escapes the medical routine to which a health team is prepared. Symptom of a war symptom in which the whole world is turned up to head - where it should not extend improvisation or disorganization; Where the lack of organicity between commands and the various links of a plot that is composed of the combatants of different echelons can generate a fatal misconception, an unforgivable strategic error that will inevitably result in the sacrifice of the innumerable human lives.

Let's look at the testimony of Daniel Terzano:

It had snowed all night and followed snowing, the earth was totally white and our uniforms could be seen a thousand kilometers away. Not so far, just five hundred meters on the hills in front, while we started our last withdrawal (it was the dawn of June 14) we saw a row of English commands walking just over the mound crest: they walked slowly, no doubt with the Safety of the mission to fulfill, and almost with the absolute certainty of triumph. On the other hand, we were marched quickly on the snow, south, to locate ourselves on the other side of the hill and so it wasn't seen so easily… And that was all we knew we had to do: there was no mission anymore, Only the precipitate, the erratic, the look one and the back, the pure improvisation of survival. (…) So, little by little, without anyone transmitted and no one disobeyed to an order, our direction was twistingly twisting, distractedly, to the west, to the people. Explicitly no one said anything, but the instinct, this cold, white morning of defeat, was invisibly guiding our steps to the place where, by surrender or massacre, would end everything. 13

Although the heroism and bravery of those who fought, or speaking otherwise, for this reason, is always highlighted by the immense gesture of devotion of those who were there as anonymous protagonists, sometimes and At so many times, the unpreparedness and disorganization of military commands, or the political capital with which such commands sought to raise themselves for their mistaken choices are equivalent to crimes of Lesa Fatherland or Lesa Humanity.

It was June 14, 1982. Let's look at this excerpt from the “dialogue” between General Mario Benjamin Menéndez, Military Commander of the Argentine Armed Forces and Governor of the Falkland Islands and the de facto president, General Leopoldo Fortunato Galtieri:

Gal. Benjamin Menéndez: (…) and knowing the responsibility I have to assume, I feel the need to express you all that I said a possibility that I believe viable, which I see as viable. The other clarifies you, general, that as commander I do not see it as viable. I was in the middle of the troops right now, before talking to you, I saw the troops fighting on battle fronts when there is no way to do it… I saw heroes taking and bringing what they can. Perhaps there are also people who retreated because there was no ammunition, many people have been overwhelmed for lack of ammunition… my general, this troop can no longer require more after what has already fought. I had told him yesterday that… this… last night and today would be crucial. We are at noon today and this is as I had expressed it. We have not been able to keep the detachments advanced, we have no space, we have no conditions, we do not count on the support we need and, I believe, my general, who we have to assume a great responsibility to the soldiers will continue to combat a combat without possibilities on time of a few hours more and will cost many lives. This must communicate as commander in Falklands. Exchange.

Galtieri:… ( silence)

Benjamin Menéndez: I have nothing more to clarify, my general, I wanted to know if I can wait, after your reflections, that you answer me something. Exchange.

Galtieri:… ( inaudible )

Benjamin Menéndez: My General, I thank the last word, but really, in the last hours of today, I don't know what will be the Falklands anymore. And in this I am willing to assume all the responsibilities that may then fit me. If you have nothing more for me, I cut and that's it. 14

4

According to Silvia Barrera was a shock, as if they all suddenly disinfect when the cease was announced, the surrender of June 14. They didn't even think of this possibility. It had been a few days since they had left their foundations in Buenos Aires thinking that Argentines were keeping their positions in the theater of operations, not that they were winning the war, but they were holding the British's advance and ensuring the defense of the territory. And since then, everyone from the hospital ship health team had to act very quickly and skill. They saw many Argentine combatants humiliated on the beach, in short shorts, at a temperature of five degrees below zero; The British demanded that they would arrange for all uniform and weaponry. How and how much they could, in the irreat, they sought to bring on board the largest possible contingent of Argentine soldiers so that they would not fall prisoners. And they went on this mission until June 18 when the food was over - the ship was full in its maximum load. On the 19th, they landed in Comodoro Rivadavia. On the ship, the work was still incessant. In addition to the numerous injuries, this picture was watched in diarrheal state - it is that numerous soldiers about two months ago only took water in the ponds on the Falkland islands. On June 20, they arrived at Palomar airport at night to avoid the presence of reporters.

Silvia states:

The next day we came to work as if nothing had passed us. No one asked us anything. Everything had already become a thick block of silence. The order was that no more from Falklands was spoken. The men who were welded were not wanted to hire because they said they suffered from post-traumatic stress. And the men were silent to get work. There have been many cases of former combatants who committed suicide. Our group of surgical instructors, when we come back, followed in automatic in our tasks, and over time, we got married, we had children, we were busy with our families and obligations. And all journalists, television programs, did not matter to them what concerned the subject of Falklands.

Silvia also says that the army made them sign a confidentiality document in which it was mentioned that we could not tell anything, absolutely nothing, of what they had lived. Already when they went down in Comodoro Rivadavia, all were put in line, and went to a table in the one that there was a soldier who told them ‘You have to sign here’ And everyone had to do it. If this was a strategic way of preserving a military secret, it was also a way of repressing/recalcating their experienced experience, this block of past that, according to Silvia, has always returned to them strong and intense. For years in a row, they remained silent after more than a decade began to speak those who were more resilient. Beginning to speak, process in their heads what had been lived, how those months, those weeks, those days who never sinks into the distant and untouched past were lived. And in such a way that even today, more than forty years old, there are those who can not speak. Of the six, there are people who say nothing. That preferred to stay silent. Silvia Barrera was the first to witness, and never stopped doing so. She says you need to know much more than to know those of their generation.

Before we said goodbye, after the photograph ballooned to the personal archive, I ask Silvia if she volunteers once again if, by chance, the fate of Falklands demanded her effort and sacrifice. She laughs sneaky and sincere and answers me Of course, and it would be easy, I'm ready, Falklands is in me.

This text expresses the author's opinion.

Grades:

- Cf. Muñoz, J. Barco Hospital - Military Health in the Malvinas War. Malvinas Collection. Buenos Aires: Argentine Editions, 2017 (p. 44). ↩︎

- The same, p.85. ↩︎

- Interview with Silvia Barrera by André Queiroz, held on November 19, 2023, at the Central Military Hospital in Buenos Aires. ↩︎

- Idem ↩︎

- Idem ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎

- In: Speranza, G. & Cittadini, F. Gurerra Party: Malvinas 1982. Buenos Aires: Ensayo Edhasa, 2022 (p.115-116). ↩︎

- Same, p.116 out of 121. ↩︎

- The same, p.116-117. ↩︎

- Cf. Terzano, D. 5,000 goodbye to Puerto Argentino. Buenos Aires: Editorial Galerna, 1985 (p.69-70). ↩︎

- Interview with Silvia Barrera by André Queiroz. ↩︎

- Idem. ↩︎

- Terzano, D. 5,000 goodbye to Puerto Argentino. Op.cit. (p.103-104). ↩︎

- Cf. Malvinas: surrender - Menéndez's last dialogue with Galtieri. Access Link: https://youtu.be/DSFqx3Tnr24?si=wqTNYQc9-qwc1Hc0 ↩︎